Summer School

This is a story about extraordinary people; it begins with the confusion of one very ordinary person.

You know how sometimes you see someone and you know you’ve met them before but you can’t quite place them, and of course they recognize you because they’re normal human beings, and you’re wracking your dumb little pea-sized brain, all three brain cells squinting at each other, each one hoping another will come up with something, this nice lady is so familiar, and maybe you’ve almost got it, one brain cell, ol’Winky, can always count on that one, is tentatively raising a hand to maybe ring a bell, but then this whole class of seventh graders comes spilling in and it’s barely 8 am and now any hope you had of focusing on this smiling lady, who IS she, is swept away by the noise of scraping chairs and desks and a dozen or more 12-year-olds starting their school day—you know that feeling?

I’d blame the early hour or the lack of caffeine or the general chaos of summer school but the truth is, I’d been up for ages, had two cups of coffee, and these 7th graders were pretty well behaved. It’s just that when a high school English teacher shows up at a middle school on a muggy July morning, pre-8 am and ready to volunteer as a writing coach, well, perhaps you too would be so gob smacked that your brain might have to stutter and restart before you could get past your confusion and let your realization that it was her, Ms. Clarke was here, blossom into delight. Ol’Winky practically cheered: we did know exactly who she was, and wow were we happy to see her.

Backing up for a moment: I’d recently interrogated a 5th grade teacher about her experience with Behind the Book and she surprised me by singling out our writing coach volunteers as one of, if not the most, impactful elements of our programs.

“You have no idea,” she told me over and over again, “you have no idea what it means to these kids to have someone paying attention to them.”

She told me about one boy in particular who was just angry all of the time, always tight and coiled with rage. The day our writing coaches came to his class, he started out as usual: hunched, withdrawn, glaring suspiciously at the woman who introduced herself to him and two other students. When she asked if he wanted to share his draft with the group, he snapped out a no and went silent again. But, over the course of the hour, the teacher told me she watched this boy ease cautiously out of his shell until he looked like every other kid in the group, until he was responding to the volunteer’s questions with enthusiasm, until she saw him bend his head intently over his paper, pencil gripped firmly in hand. His guard had dropped, this total stranger showing nothing but genuine interest in him. She wasn’t judging or scolding or grading him, she was accepting him just as he presented himself.

In recounting this story the 5th grade teacher had tears in her eyes, remembering how for that hour, this boy had someone show him that she cared, and how quickly that adult—not a teacher, not a parent—gained his trust because all he needed was for someone to make the space for him to give it.

I remembered that story when the penny finally dropped and I realized who this oh-so-familiar woman was. She was Akilah Clarke, and I’d been a volunteer in HER 12th grade class back in the spring—I’d even written about that experience—and now, here was Ms. Clarke giving a morning of her summer break to come volunteer in a classroom, even a school, not her own.

“You’re here,” I said stupidly, grinning like a maniac, and Ms. Clarke, bless her, nodded at me encouragingly. “You’re here!” I said it again, just to make sure it was real.

“I’m happy to work with the students who need the most help,” she told me, her manner calm and her smile as open and friendly as I remembered.

True professional that I am, I turned to Sarah, our college junior/programming intern and said, quite distinctly, “Holy shit.”

I should not have done this, I realize, but I’m pretty sure none of the kids heard me.

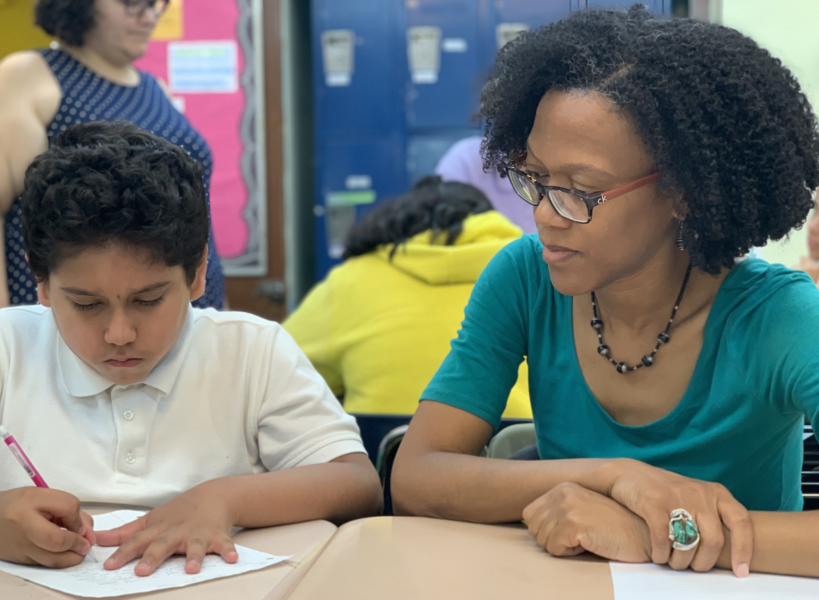

And indeed, Ms. Clarke took our most challenging students and for two hours, I watched their faces as she quietly, skillfully made them comfortable and then went about guiding each to wherever he needed to be with his writing that day. (In a class of 7th graders, the most challenging kids are almost always boys.)

We had other really terrific volunteers in the room, including a woman who was an actual literacy coach, and later I would hear so many inspiring and heartwarming stories about how positive and productive that day was from students and volunteers both, but there was something about having Ms. Clarke in our room—a teacher, volunteering on her time off!—that really put me on my heels.

In fairness, the whole experience had been a whirlwind for me. I was filling in as a pinch-hit/last-resort program coordinator, 5 classes as MS 223 all jammed into 11 days in July. The author for these four classes of 7th graders, the unbelievably unbelievable impossible-to-describe Torrey Maldonado, is also a teacher in the DOE, and we’d only been able to work with him because it was summer school and he could do the author visits, which are always during the school day. Our students were reading his novel Tight, about a couple of middle school boys who live in the projects of Red Hook, Brooklyn, where Torrey grew up. He wrote the book, he told us, because he wanted to see someone who looked like him on the cover of a book and to tell a story that reflected his own lived experiences—to be a mirror and a doorway for kids like the one he was.

The book resonated with the kids, even more so after Torrey’s visit. After the intros and a few minutes of patter, Maldonado did this thing with each class where he got real serious (and because—as the students were thrilled to discover—he bears a resemblance to The Rock, his serious look is pretty serious looking) and then he’d ask, “Ok, for real, who here has played ‘Ding, Dong, Ditch’?” Each time the kids went crazy, hands shooting up in the air, everybody laughing, because of course they’ve played “Ding, Dong, Ditch” and there was something about Maldonado’s affect that made it immediately clear he had, too.

He used that credibility, that energy, to navigate students into a conversation about how easy it can be to make bad decisions and how peer pressure actually happens—kids saying “What, are you soft? Are you afraid?” or “I thought you were cool!” or “He’s just a baby, he’s just a little ____.” He got the students talking about his characters making the wrong choices, sometimes by accident and sometimes on purpose, and then got them unpacking those motives. Most importantly, he showed that someone like them could grow up to be him, and something in his intensity made me certain he was constantly aware of and working toward that responsibility, not just in our classroom but every day of his life.

That’s what I thought about when I watched Ms. Clarke sitting patiently, listening, as a kid in her group haltingly read his draft aloud. He stumbled over words, lost his place, had to stop, and her quiet attention gave him the space to start again. The other kids at the table mirrored her pose and I thought of some of my favorite teachers growing up. They were the ones who made me want to be better for them, the ones who brought something extra to their work and made me want to do the same. Ms. Clarke; Torrey; Ms. Rosado, our classroom teacher, they all had that something about them that showed us, each in their own way, just how much they cared, and their capacity for caring seemed bottomless.

It was humbling to have this experience, not least because I’d taken an instant dislike to this one kid in particular and each hour I was with him I tried so hard not to be annoyed by him but in the end, though I was 42 years old and he was TWELVE, I finally just had to avoid him because I couldn’t stand his smug little face. How these teachers managed to spend full school years with kids like him, finding not just the patience to deal with them but real empathy to care for them as well as the 29 or so other individuals in the room each period—well, I’m sure these people are human, too, but they sure didn’t look that way to me.

So maybe that’s why it took me so long to put a name to Ms. Clarke’s face—I do believe that angels walk among us, I just didn’t expect to see one on a hot July morning at MS 223 in the South Bronx. But I shouldn’t haven’t been surprised, because there were angels everywhere that month, from Ms. Rosado to Ms. Clarke to our teaching artist, Candance, to all the volunteers who made time for us, to Denise and Myra at Behind the Book who went several extra miles to make sure the programs were set up for success, them pretending so nicely that I would be fine to handle the job but then sending me the most angelic angel of them all, Sarah, balancing her out with the impish angel that is Torrey Maldonado—there were angels everywhere: it just took Ms. Clarke showing up for me to see them.

In conclusion, if you want to have your life changed, if you want to experience that transcendent inner peace and joy that comes from seeing overwhelming good happening in the world, I would highly recommend spending an hour or more in a classroom with us. I can’t guarantee you’ll come away rapturous, especially if you end up with that one irksome kid, but I’m willing to bet that if you make the space for them, as you’re listening to a kid tell you his story, opening himself to you, this stranger, trusting you to listen and to hear him, you’ll recognize the angels all around you, and maybe even have a flutter of feeling like one yourself.

by Casey Cornelius

More of Casey’s writing is on her personal blog, here.